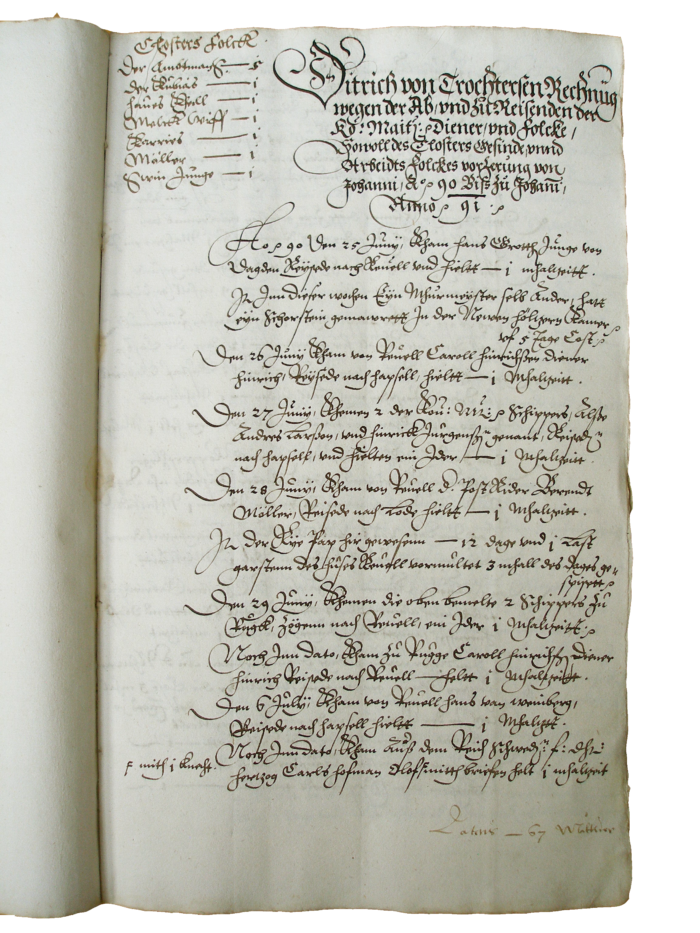

s long as the former monastic complex retained its military significance, it was repaired and fortified from time to time, and large amounts of weapons, ammunition, powder, etc were kept within the monastery walls, carefully listed in the inventories every year. In the 1590s (and later) the manor members, who received wages or who were supported by the crown throughout the year, numbered only 11–13. Of them five were the bailiff Trochterssen with his wife, his child, his valet and his maid, and the rest included a labourer, a miller, one or two reeves, a herdsman, a herdswoman, a cellar girl, and a pig boy, as occasion required. Other tradesmen such as bricklayers, carpenters, cobblers, etc were invited to the manor when needed. The bailiff’s wife, who was also on the payroll, played an important role in the manorial household, as the monastic complex, which was situated on an important traffic route, offered board and lodging to the travellers. A baker and a brewer supplied bread and beer, if necessary. The baker Hindrick lived near the church in Harju-Madise in the 1590s and, for example, in 1599, baked bread for Padise every fortnight; the brewer was on the manor for 36 days during that year, while the blacksmith worked on the manor for 16 days. An overseer in charge of threshing and crops lived on the manor seasonally. Very often Estonian trades names were used: (kubijaß, kubis ’reeve’; karis ’herdsman’; Rije Papp ’overseer’) as well as place names and personal names (Soijawhe/Sotawe Andres’ the military man’).

The inventories listed all the foodstuffs and spices that were bought, the animals annually slaughtered, and all the seeds sown into cabbage and herb gardens on the manor. The manorial management and accounting reports used 5–7 books of paper annually (1 book contained 24 sheets).

The inventories listed all the travellers who stayed at the manor and ate and fed their horses at the expense of the crown. By midsummer the bailiff made a full list of the guests (Gasth-Register). The list included all kinds of local dignitaries, their couriers, clerks, and clergymen (for example, the visitation to the church by David Dubberch) and other travellers, who journeyed from Tallinn to Haapsalu, Hiiumaa and Riga, or the other way round.